My most recent traveling was not work related, but for vacation, to celebrate the New Year in Sicily. This was my third time traveling to Sicily; however, the island nation never ceases to fascinate me.

Taormina and Castelmola

The more I travel to Italy, the more I realize that it is not really a united country but remains a loosely connected group of small nation-states. The unification process that made Rome the capital in 1875 still has not succeeded in overcoming the ancient fortress walls of regional identities, traditions, and socio-political structures which refuse to surrender to an all-encompassing nationalism. So here I am writing about my impressions of just Sicily, mainly centered around a little town lovingly called “Giajé” in the Sicilian dialect, known more formally as Giarre. The town is located on the eastern side of the island, nestled between the majestic volcano, Etna, and the Mediterranean Sea.

Etna and the port city, Riposto

For me Etna is a perfect metaphor for Sicilian culture. It is the tallest active volcano on the European continent and stands proudly alone, as if it decided to venture away from the clutter of the Alps and reign supreme over its own island. Similarly Sicilians seem proudly independent and content to be slightly isolated, surrounded by the beauty of nature and the richness of their unique culture. However, over history Sicily has not had the luxury of long periods of independence due to the island’s strategic location.

Chiesa di San Cataldo in Palermo – Byzantine, Arab, and Norman architectural style

The island has been repeatedly conquered and re-conquered by different empires – the Greeks, the Romans, the Byzantines, Berbers, Arabs, French, Germans, Spaniards, Austrians, and so on. Finally in 1860 Giuseppe Garibaldi conquered Sicily as part of the Kingdom of Sardinia which soon became the Kingdom of Italy in 1861. Perhaps all of this history of constant battles has helped to forge the fiery spirit of Sicilians.

View from Castelmola

Like the volcano, I have found that many people from Sicily are generally cool and calm, but occasionally erupt into heated discussions which, at least to an non-fluent outsider, seem like a furious battle of wills. However, in reality it is most likely just a regular discussion on differing opinions on any topic – from politics to the best place to buy fish. For an American, used to over-polite conversation, this culture of emphatically speaking your mind is both intimidating and refreshing.

Etna explosion December 2013, picture from www.dailymail.co.uk

The other enduring legacy of multiple invasions is a diversity of architecture that makes each town in Sicily unique and unforgettable. I am not an expert in Italian architecture by any means and I know that there is an abundance of stunning art and architecture throughout Italy; however, I still hold that Sicily has many less famous, yet equally astonishing cathedrals, domes, theaters, castles, arches, and beautiful little streets and markets.

Ragusa Ibla

Siracuse Ortiga

Greek theater, Taormina

Then there is one thing Sicily is infamous for, the notorious Sicilian Mafia, or Cosa Nostra. There is no denying that the mafia existed and continues to exist in Sicilian; however, thankfully, in day-to-day life or for the passing tourist, the mafia is nothing more than a harmless shadow that doesn’t cause any trouble, unless you go looking for it or start a successful business. As an American, an interesting bit of history is the fact that Americans were quite supportive of the Italian mafia during World War II. As the saying goes, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” The mafia was the enemy of Mussolini’s fascist rule, and therefore worthy of support in the Allied effort to invade Italy.[1] However, this is just one of many factors that have contributed to the resilience of the mafia in Sicily. I have a fascination with the culture of organized crime, but will leave further discussion of the role of the mafia in Sicily for a separate blog post. A good book about the mafia is “Gomorrah” by Roberto Saviano. This book is a beautifully written non-fiction about the Camorra, a mafia based in Naples. “The Godfather” may have made the Sicilian mafia famous world-wide; but organized crime is certainly not a unique Sicilian phenomena.

Finally, not to end this blog on a down-note and not to leave out one of my favorite things about Sicily, the food is amazing! Pasta, fresh fish, fresh baked bread, 100% pure orange juice (spremuta d’arance), granita (a delicious sweet summer breakfast), espressos, the list goes on. One phrase I’ve learned well is… mangia, mangia, mangia (eat, eat, eat)

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collaborations_between_the_United_States_government_and_Italian_Mafia

El Salvador is an unchartered and yet a familiar destination for me in many ways. I grew up in Manassas, Virginia, where the immigration from El Salvador has quickly turned from a trickle to a steady stream. During my college years, every time I returned home there would be a new pupuseria (a restaurant selling the traditional delicious tortilla with cheese, chicken/meat and/or beans with a cabbage salsa on top) to try out. I also have two friends from El Salvador whom are both artists – one is a poet and the other is a graphic designer – both capoeristas.

My excitement to travel to El Salvador was tempered by the grim reports of high homicide rates and gang violence. During high school I had become all too familiar with the notorious gang MS-13, or the Mara Salvatrucha, a transnational gang who unfortunately also migrated from Central America to the US despite the fact that the majority of immigrants from El Salvador came fleeing the violence at home.

It must be hard to leave such a beautiful country. San Salvador is surrounded by beautiful volcanoes and mountains, tucked away but not far from the ocean. The city does not boast amazing architecture but there are some hidden gems. Including the “Iglesia el Rosario,” a unique church built using the simplest materials – concrete, stained glass and iron – to create a breathtaking, deeply spiritual space. Ruben Martinez, who designed the church, had to receive permission from the Pope to construct it due to its non-traditional structure. While it is not an attractive structure from the outside, the inside is spectacular.

There is a public park with a beautiful art gallery hosting the work of Adis Soriano, a female El Salvadoran artist who combines a modern abstract style with the strong colors and focus on nature that draws inspiration from indigenous Latina American traditions. In addition the park hosts a memorial with the names of people who were killed or disappeared during the long civil war, from 1980 to 1992.

Some of the roots of the conflict can be traced back to the 1930s when El Salvador’s military dictator, Maximiliano Hernandez Martinez, led “La Matanza,” a brutal suppression of a rural uprising killing over 40,000 indigenous people and political opponents. The legacy of one of the leaders of the 1932 uprising, Farabundo Marti, is clearly remembered as his name is enshrined in the name of the rebel groups who fought the government in the civil war in the 1980s and have now become the ruling political group, Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMNL).

El Salvador faces major challenges, including high rates of inequality, poverty, and violence, as evidenced by some World Bank statistics:

- GINI Index is 48.3 in 2009, where 0 is equal and 100 is the most unequal

- 8% of the population was living below the national poverty line in 2009; and

- Fourth highest homicide rate in the world according to UNODC statistics in 2012 of 41.2 per 100,000, following Honduras (90.4), Venezuela (53.7), and Belize (44.7).

While the rate of violence is extremely striking, it is not a definition of the El Salvadoran people. I would also venture to argue that this violence is more a product of the impact of the illicit drug trade than any other factor. I believe the solution to decreasing violence in Central America cannot be separated from a careful analysis of how to decrease or control the demand for illicit drugs in the United States. The U.S. is by far one of the largest consumers of illicit drugs and the illicit traffic of drugs to meet this demand has had devastating impacts on several Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, Colombia, and El Salvador.

However, to say that part of the responsibility resides with the United States is not to say that communities impacted by drug-related violence should ignore the issue nor that they are currently doing that now. During my short stay in El Salvador, I had the good fortune to visit a community outside of San Salvador where an artist center has been established that offers free classes to youths in the community. I believe that providing opportunities for young people to find an outlet for self-expression, encouragement to discover their own identity, and a space of mutual respect can go a long way to preventing recruitment to criminal gangs. I have tried to capture the beauty and power of the art these young people have created in the pictures below; however, it is impossible to capture the feeling of peace I found in this art center tucked away among the mountains. I wanted to stay and learn from these artists. I hope to one day return.

All countries have a rich culture and history; however, Ethiopia is one of a few other African countries that can claim to be the motherland of all humanity. Archaeologists uncovered the oldest bones of the closest hominid relative to today’s homo-sapiens in Ethiopia, those of Lucy, our mother from over 3.2 million years ago. So even if I stood out walking on the streets of Addis, it was welcoming that some people would call me “sister.” We are after all one extended family.

Ethiopia is not only blessed by a culture with deep historical roots, it is also a place where this history is celebrated with pride. Unlike the majority of the continent, Ethiopia was never “colonized” for a long period of time. The Italians attempted twice to colonize Ethiopia without much success. In the 1880s, Italy failed in an attempt to colonize Ethiopia, then known as Abyssinia. Later, in 1936, Mussolini successfully annexed Ethiopia. However, the Italians only held the country for five years. The Ethiopian guerrilla fighters, supported by Allied Forces, succeeded in returning the Ethiopian Emperor Halie Selassie to his throne by 1941.

In addition to pride in their independence, many Ethiopians also take pride in their deep-rooted religious traditions.[1] Ethiopian kings claimed ancestral lineages connected to King Solomon and Queen Sheba through their son, Ibn-al-Malik (also referred to as King Menelik). According to legend, Menelik went to visit his father, King Solomon in Israel. He returned home with 1000 people from each of the 12 Tribes of Israel and with a stolen artefact, the Ark of the Covenant. Supposedly King Solomon had a dream that it was the right of his son to have the Covenant and the King decided to keep its disappearance a secret. Thus the legendary Covenant has rested in Ethiopia ever since (maybe).

Palace of King Menelik II on the highest peak of Mt. Entoto overlooking Addis

Kings claiming descent from Solomon ruled Ethiopia from the 10th century BC up until the overthrow of Haile Selassie in 1974, or for over 3000 years. Whether these legends and ancestral lineages are 100% accurate is difficult to prove as there are few written records. The legends are mainly substantiated by one book written by Ethiopian scribes from early 14th century called the Kebre Negast. Regardless, the legends supported the role of Ethiopian Kings as religious and political leaders, played a part in the development of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, and help explain some of the strong links between Ethiopian Christianity and Judaic traditions. Ethiopia is also home to deep rooted Muslim religious beliefs. In AD 615, several of Muhammad’s followers fled and settled in southern Ethiopia. Muslims and Christians co-existed peacefully until tensions and a series of wars broke out around 1290. [2]

St. Mary’s Orthodox Church

Mosque

A final remarkable aspect of Ethiopian culture is its diversity between regions. There are over 80 languages spoken across the country according to the 1994 Ethiopian census. Each region of the country is unique with different languages, food, dance, and beliefs. This is part of the reason that I am eager to return to Ethiopia with more time and the ability to travel to various historical sites in each of the regions – from the famous carved stone churches of Lalibela, to Lake Tana, the birthplace of the Nile River, to Shashemene, home of a large Jamaican Rastafari community in the South. This short list does not come close to doing justice to all of the natural beauty and cultural richness that I have read about and hope to one day see firsthand in the regions of Ethiopia outside of Addis Ababa.

In between work over the past two weeks, I spent my time just trying to get to know a little bit about Addis Ababa (Addis). It is a large, lively and chaotic city. The chaos has a lot to do with all of the construction going on, as well as the fact that apparently streets have multiple names and few signs. Chinese investors are helping to build roads and even an above-ground metro line in the city. While the end result is likely to be a more modern city, the current status is one of disruption. Roads are often closed without warning, stoplights sometimes do not work, and there is mud everywhere. There are also frequent power-outages in the city and internet is pretty unreliable.

It is hard to keep your shoes clean with so many roads under construction!

Despite these challenges, Addis remains a welcoming city. People are very friendly and crime, especially violent crime, is remarkably low. As a foreigner and a white woman, I stuck out a lot and would get some extra attention, particularly when trying to go running with a colleague in the afternoons. However, when running people would normally just clap and offer encouragement. I never felt threatened. Only one colleague had anything stolen – a camera cleverly picked from his pocket by a 5-6 year old boy while his friends created a distraction. This kind of petty crime, while unfortunate (I’m glad it was not my camera!), is to be expected almost anywhere and particularly in a place with high poverty rates.

Boy playing with a tire in a small street

According to the World Food Program over 49% of Ethiopia’s population is malnourished (Addis: putting food on the table). Ethiopia suffered from large scale famines in the 1970s and 1980s, when droughts combined with the failure of government policies to support the poor and conflict led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians.[3] While I was in Ethiopia, there was a large conference being hosted by IFPRI on Food Security in Ethiopia. In addition to high rates of malnutrition, Ethiopia is also plagued by high incidence of HIV and malaria. On the bright side, things are moving in the right direction. According to the World Bank, the percent of the population living under the national poverty rate decreased from 38.9% in 2004 to 29.6% in 2011. Prevalence of HIV as a percent of people ages 15-49 who are infected with HIV decreased from 2.9 in 2004 to 1.3 in 2012. Current political stability and the leadership of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, peacefully elected in 2012, will hopefully contribute to keeping trends in reducing poverty, malnutrition, and disease in the right direction.

Pictures from largest open-air market in Africa in Addis

What I am sure of is that despite the struggles of day-to-day living in Addis, the culture and pride of the people remains vibrant and apparent everywhere. I enjoyed eating the delicious local cuisine of injera (round bread made from teff flour), doro wot (spicy chicken), tibs (spicy meat), and tej (honey wine). I also had the privilege of going to a traditional restaurant where performers played traditional music and danced traditional dances from the various regions of the country. I got a little taste of Ethiopian jazz and “funk” infused with traditional sounds at a place called “Jazzamba” (Check out this BBC special on the unique Ethiopian music scene). Finally, if you ever want to crash a really fun wedding, look for an Ethiopian wedding. They go ALL out. While I was there I saw several wedding parades on the streets (slightly annoying because they block roads and film the entire precession!) and had the opportunity to slip into the back of a wedding being held on the grounds of the historic Saint Mary and Saint George Churches.

[1] Historical references are based on the book “History of Ethiopia” by Harold Marcus (1994) and backed up by what I heard in Museums in Addis.

[2] According to the national census conducted in 2007, over 32 million people or 43.5% were reported to beEthiopian Orthodox Christians, over 25 million or 33.9% were reported to be Muslim, just under 14 million, or 18.6%, were Protestant, and just under two million or 2.6% adhered to traditional beliefs (source: Wikipedia).

[3] The droughts in 1973 contributed to the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie by the Communist Regime called the Derg which was later overthrown in 1991.

I had never been to the African continent before my recent work-related two week trip to Rwanda. Based on news and stories about African countries, I expected to encounter a chaotic and colorful landscape. I was also slightly apprehensive, knowing that my arrival would coincide with the 20th year following the Rwandan genocide of 1994. Arriving in Kigali, Rwanda I encountered a welcoming city with smooth, well-marked roads winding among green hills. I was struck by the feeling of calm and peacefulness and yet everywhere I saw grey signs with the word “Kwibuka” – meaning “remember” in Kinyanrwandan, the national language along with French and English.

Typical road in Kigali:

Fountain with “Kwibuka 20” sign in the bacK:

It is incredible the distance this tiny country in the heart of Africa has come in just two short decades. In 1994 Rwanda exploded into one of the bloodiest 100 days the world has ever seen. 600,000 people were brutally murdered in an attempt by the Hutu to wipe out the minority Tutsi group. Before arriving I had watched the movie Hotel Rwanda and been moved by the depiction of the struggle to survive during this horrendous tragedy; however, being in Rwanda and participating in events to commemorate the individuals who lost their lives and the pain of their surviving family members made a powerful impression on me. I began to be filled with questions. Why did this happen? What was the role of the international community? How have people, many my age, who have experienced such trauma been able to move forward with their lives? What can be done to prevent future violence?

Hotel Des Milles Collines: real hotel from movies “Hotel Rwanda”

Why? Some people have a terrible misconception of Africans as violent people based on the fact that most of what we see about the continent in western media is saturated with stories of conflict and instability. I have experienced a similar frustration when I tell people that my mother is from Colombia and they make some comment about cocaine or guerilla warfare. I don’t believe that the inhabitants of any country are inherently more or less violent than any other. Violence is the response to a complex mix of factors including history, social pressures, injustice, inequality and lack of strong mechanisms and traditional means for resolving conflict peacefully.

In Rwanda, the Belgian colonizers intentionally sowed the seeds of conflict by formalizing ethnic distinctions among the Hutu and Tutsi and then favoring the Tutsi. Under the colonial rule of Belgium, Tutsis were identified by a fine distinction between more those with more “European” pointy noses and Hutus as those with wider “African” noses. The Tutsi elite were given ownership of land, better education, and opportunities to work in the government. The Belgian gave everyone identity cards that identified people as either Hutu or Tutsi. Does that mean that the colonizers bear all of the responsibility for the violence that ensued. No, after independence no Rwandan leader stood up to end the discrimination based on an imaginary ethnic identity. Rather the post-independence governments continued to require the identity card that identified ones ethnicity and instituted discriminatory policies against Tutsi. On the radio, in the schools, in government sponsored messages the Tutsi were referred to as snakes and cockroaches to be exterminated. An extremist movement took hold, armed with a dehumanizing rhetoric to refer to the enemy, machetes, and automatic weapons purchased from France.

The French government has been accused by the current Rwandan President of supporting the government that orchestrated the genocide and of continuing to protect some of those involved in the genocide from facing justice (The Guardian news article). This brings me to my second question, where was the international community?

During a commemoration to honor 26 Rwandan USAID staff killed during the genocide, I was touched by several of the speeches given but one speech by a Rwandan USAID staff member really stands out in my mind. He started off saying that he had reluctantly read the book of testimonies thoughtfully collected from the families and friends of those who had been killed with the hope that he would find one inspirational story of courage and kindness, but he found none. So he told another story. He reflected on a story in the collection of testimonies of a Tutsi woman, a USAID staff worker, who had walked miles and miles with her two children to escape the violence. On the road, a car stopped and one of her fellow USAID staff members, a Hutu, asked where she was going and offered to drive her to where she hoped to find safety with an American family who she had gotten to know and she hoped would shelter her and her children. Grateful for the help, she got in the car with her colleague and arrived at the residence. No one was home, but there were some other Tutsis hiding there hoping that the Hutu militias did not know that the American family had left. The next day, the same Hutu USAID staff member came back with a group of militia and killed his colleague and others who were taking shelter in the house. Yes, the speaker stated, this is our history. We cannot hide from it. He was saddened by the cruelty fellow Rwandans, his fellow countrymen, were capable of inflicting on their own, their own colleagues, neighbors, and friends. I was saddened by the ability of American USAID workers to abandon their colleagues in their greatest time of need. Fleeing at the time when their simple presence could’ve meant the difference between life and death for those they had worked alongside for years.

David Mugiraneza

Age: 10

Favorite Sport: Football

Enjoyed: Making people laugh

Dream: Becoming a doctor

Last word: ‘UNAMIR will come for us’

Cause of death: Tortured to death

Of course one cannot take responsibility for all of the cruel and cowardly actions that our compatriots have taken in the past but this led me to a second question. What would I have done? When the genocide began all foreigners, all “muzungos” (white people), were evacuated. All Americans left, except a few, including Carl Wilkens. I have read his book “Why I stayed” and it is an incredible testament of bravery, though humbly written. He does not hide his fears, nor his intentions. He had to defy the orders of the US government to evacuate. He stayed as an individual person, knowing that he would not receive any protection from the American government. He stayed because he knew that if he left, the two Rwandan Tutsis who had helped to raise his children and with whom he had developed close friendships would be killed. If he could only save two lives, this was enough. He also had a strong faith in God’s protection. He sent his wife and three children to Kenya and stayed throughout the genocide. During those 100 days of the genocide he repeatedly risked his life in order to bring water and food to 2 orphanages, contributing to save the lives of over 600 orphans (Tutsi and Hutu). I don’t know if I would have had such courage, I do not blame those who left. I hope that I am never put in such a position and if I do find myself in such a situation I hope that I have the calm, courage, and intelligence to know what is the right course to take.

Commemoration ceremony

The other stories that deeply inspired me are those of the survivors. I spoke with Rwandans who had seen their parents killed by their neighbors. One told me that his brother was forced to watch as his Hutu neighbor killed his young boy, raped and killed his wife, and then, only then was he burnt to death. The brutality of the killing is beyond anything that can be imagined. Yet, the survivors have returned to living alongside their neighbors, the same people who committed such atrocities. How? One factor is the incredible leadership of Paul Kagame, the current President and the leader of the Tutsi RPF forces that defeated the Hutu to end the genocide. Although the Tutsi won, Paul Kagame and other leaders forced the soldiers to not take revenge. In one case, one Tutsi had lost ALL of his family members and killed the Hutu soldier who was responsible for these deaths. A natural reaction and yet one that could lead to a neverending cycle of killings. This Tutsi soldier was taken to a stadium and publically executed for committing murder. This is the example set by Kagame’s leadership. Killing is not acceptable for any reason and there is no longer a differentiation between Hutu and Tutsi. Yes, you have to live with those who murdered your family, you don’t have to like them, but you cannot kill them. A friend of mine on this trip is reading the biography of Paul Kagame. I think it is next on my reading list. He is an extremely intelligent man, though he can certainly be accused of authoritarianism. He has brought peace when the country needs it most, but peace at the moment comes with the price of lack of freedom of expression and complete intolerance for breaking strict rules. You cannot kill, you cannot walk on the grass, you cannot use plastic bags, you cannot speak out against the government…

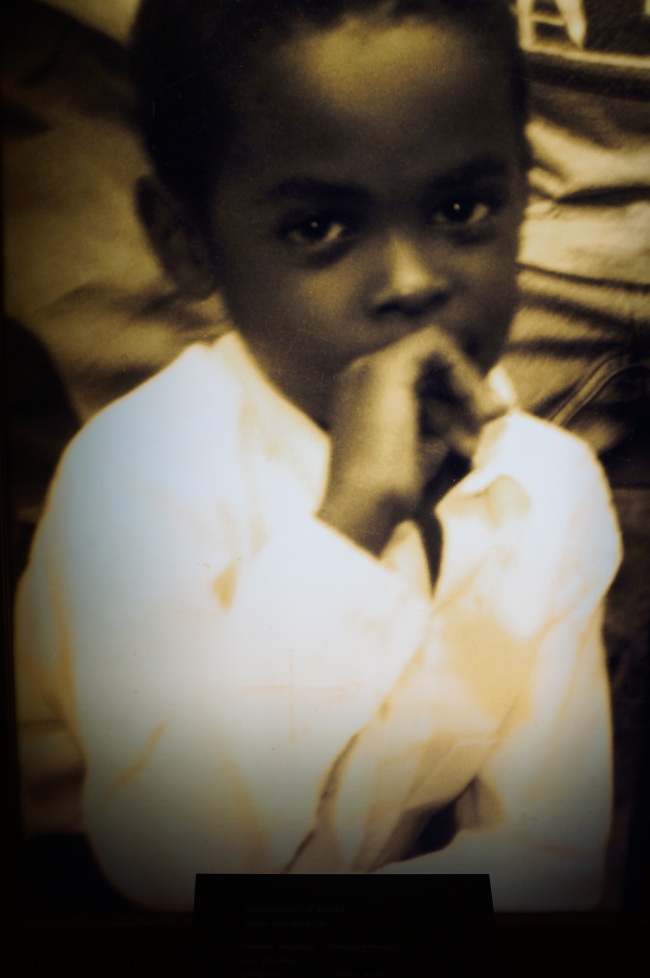

Smiling boy in a tree in Kigali

What can be done to prevent future violence? There has been a well-coordinated campaign to educate the people about non-violence, forgiveness, and tolerance. Some of the Rwandans I spoke to say that they cannot forget what happened to their families, they remain traumatized by what they have experienced, but they continue to look forward. They try to keep their sadness from turning to hate. I cannot imagine how difficult that act of moving forward must be. Yet what I feel is a determination on the part of Rwandans to keep the memory of the past and to ensure that it never happens again, that no one ever inflict such pain on another person ever again.

Their courage, resilience and dignity is an inspiration. In all of my interactions with Rwandans I found them to be very thoughtful, respectful, warm, and honest. The path they have come from is darker than I can ever imagine, yet I full confidence that the future of the country will only be brighter and brighter.

Market in Kigali

This is a renewed att empt to keep a blog. I have recently had a slight career change that will be taking me on a whirlwind tour of countries I previously knew little to nothing about. Starting in January 2014 I changed jobs from working as a Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist in Bogota, Colombia for USAID, to working on a project to launch a monitoring system for all USAID Missions starting with an ambitious list of 17 Missions in developing countries across the globe. I will be traveling to several countries for a period of two weeks in order to train USAID staff on using a new platform designed to support the collection and analysis of data on progress towards development objectives.

empt to keep a blog. I have recently had a slight career change that will be taking me on a whirlwind tour of countries I previously knew little to nothing about. Starting in January 2014 I changed jobs from working as a Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist in Bogota, Colombia for USAID, to working on a project to launch a monitoring system for all USAID Missions starting with an ambitious list of 17 Missions in developing countries across the globe. I will be traveling to several countries for a period of two weeks in order to train USAID staff on using a new platform designed to support the collection and analysis of data on progress towards development objectives.

In two busy weeks it will be hard to get to know the culture, history and people of a foreign place; however, I will use this blog to try to capture my impressions in the hopes that my life will bring me back with more time to fill-in my initial sketches.